FontysICT-sem1

Casting and ‘as’

What is casting?

An example of casting in C#

Product product = (Product) ListBoxProducts.Items[2];

From the Items of a ListBox named ListBoxProducts

the item with index 2 is read out here.

The Items are of type Object but the developer knows that all the

Items in the ListBox are of type Product,

and so wants to put this item into a variable of type Product:

this can be done by using a cast: The (Product) immediately to the right

of the = sign is the cast and indicates that whatever is to the right of it

should be treated as being of type Product.

Why is cast unsafe and should be used as little as possible?

All so-called statically-typed languages (statically-typed languages)

such as C#, Java, C and C++ support casting.

Statically typed means as much as:

Compile time (that is, at compile time), the type of each value and variable is determined.

That type can runtime (during the execution of the program)

no longer change: this allows the compiler to detect a lot of errors

and alert the developers. Developers use this as a kind of safety net.

By going caste you create holes in that safety net:

you tell the compiler: don’t interfere:

Trust me, I know what I’m doing.

A better alternative

In C#, instead of sidelining the compiler’s “Trust me, I know what I’m doing”, you can use that compiler’s knowledge.

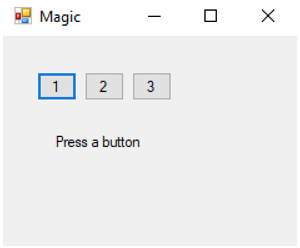

Suppose we created the following program:

As soon as a button is pressed, the label text should change to: “You pressed button: x”, where x is then 1, 2 or 3.

The easiest way to program this is to have all 3 buttons have 1 common buttonhandler method:

private void NumberButton_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Button numberButton = (Button)sender;

lblResult.Text = "You pressed button: " + numberButton.text;

}

But suppose you accidentally attach the label Click event to this method as well. Then when you click on the label you get:

Exception Unhandled

System.InvalidCastException: "unable to cast object of type ... to ... . "

Casting fails here and so your program crashes. There is a neater way to change type: with the as operator. With as you don’t say to the compiler “trust me, I know what I’m doing”, but rather you say “I think this goes, but check it for me!”. The code then looks like this:

Button numberButton = sender as Button;

The beauty of this is that numberButton now becomes a valid Button object, but if the conversion fails then numberButton gets value null.

We can take advantage of this by checking for null:

private void NumberButton_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Button numberButton = sender as Button;

if (numberButton != null)

{

lblResult.Text = "You pressed button: " + numberButton.Text;

}

}

Or neater still:

private void NumberButton_Click(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

Button numberButton = sender as Button;

if (numberButton == null)

{

MessageBox.Show("Button handler by something that is not a button", "Programming Error", MessageBoxButtons.OK, MessageBoxIcon.Error);

}

else

{

lblResult.Text = "You pressed button: " + numberButton.Text;

}

}

This way you no longer have a silent fail, pointing out the error in your program.