FontysICT-sem1

How do you program with objects?

Using Hero against Monsters

The bigger software gets, the more time-consuming the testing and maintenance. Therefore, the software world is looking for ways to make programs maintainable. One of the more successful ways is to work with objects. A team creating a Computer Game about a hero (hero) who fights monsters will preferably want to program in one place what the properties of the hero as well as what a monster is and what you can ask the monster to do.

If there are 2 samples, 2 objects are created,

if there are 8 samples, 8 objects are created.

Each of these objects represents 1 sample.

The properties and behavior of a sample is programmed into

a piece of the program that we call a Class

(class) and which (in this example)

is given the name Monster.

Example in C# (how to do this in Visual Studio comes a bit further):

class Monster {

...

}

where in the place of the dots comes the code for this class.

Example in Java:

class Monster {

...

}

Sample in Swift:

class Monster {

...

}

Indeed, these examples are the same.

You’ll find that there really are differences in how you note a class in one language or another, but whatever language you’re in:

whatever classes you create remain the same!

In many programming languages, it is agreed that the name of a `class` begins with a capital letter.

Software Engineers figure out in the beginning of a project

what objects are needed and from that follows

which classes are going to be programmed.

You can largely figure this out without knowing what language

the software will be built.

You can compare this somewhat with building a house:

Where the walls, windows and doors come (the structure) you can to some extent

imagine and draw without knowing whether the house will be built with bricks,

concrete or wood.

An object can have certain properties.

For example, each Monster will initially be completely healthy.

If the hero attacks it, the monster will

get tired or injured and

eventually may succumb.

How do I create a class in Visual Studio?

Right-click on the project and choose Add Item,

then choose a class. At the bottom of the screen you can specify the desired

class name (file name is class name with

extension .cs) and then click the OK button.

In many programming languages it is common to program each class in its own file

programming.

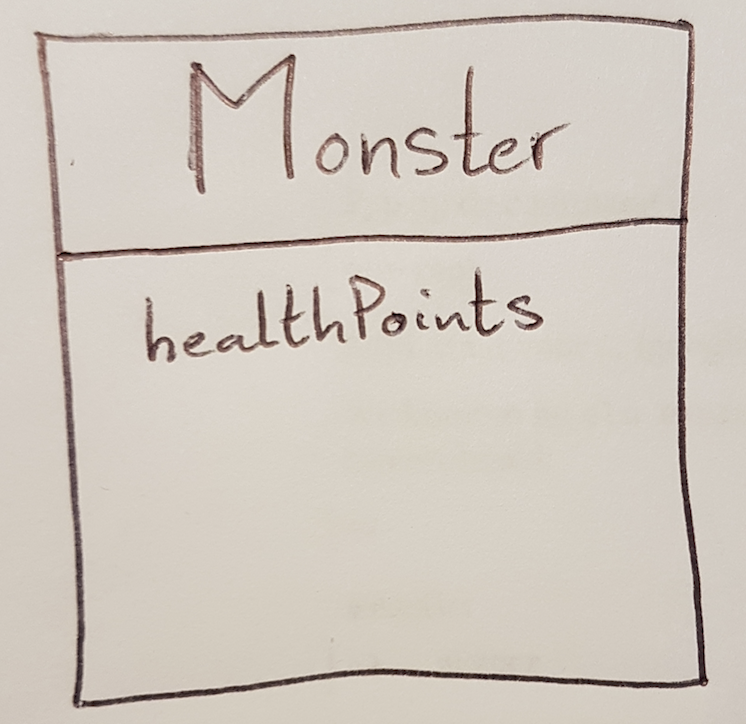

Health

In this game, we can accomplish that

by giving the monster hitPoints:

For a newly created monster, this stands at 100,

with injuries, this integer gets smaller and smaller,

at 0 the monster falls down defeated.

A value like hitPoints that each object

of a certain type carries with it

we call a Field.

For this purpose, we create a field lifepoints in Monster.

class Monster {

int hitPoints = 100;

}

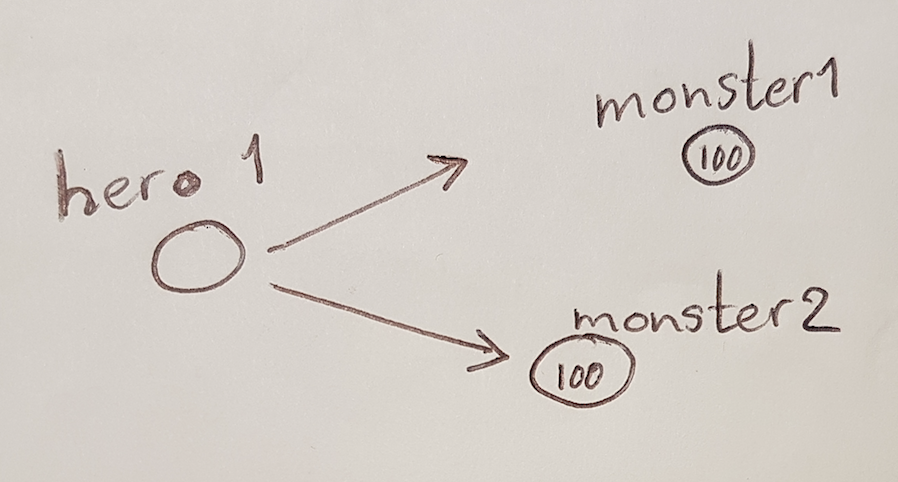

This determines that every monster has hitPoints. The value of that number may vary from one monster object to another: monster 1 may still be at 100 while monster 2 may have has only 13 left.

The code contained in a class is shared with all the objects

of that class (usually we say all objects of that type,

because a class is a way of defining a type).

To create an object of class Monster:

C# or Java:

new Monster()

(we then say it uses the new operator)

This creates an object somewhere in memory

of type Monster is created somewhere in memory, however we have no way of

to reference that object.

Compare it to a balloon filled with gas: as long as you

have the string (the reference to the balloon) you can reach the balloon,

but if you let go of the string you can no longer reach the balloon.

We can store such a reference in a Field

(also called a variable)

and that Field must be somewhere in a class:

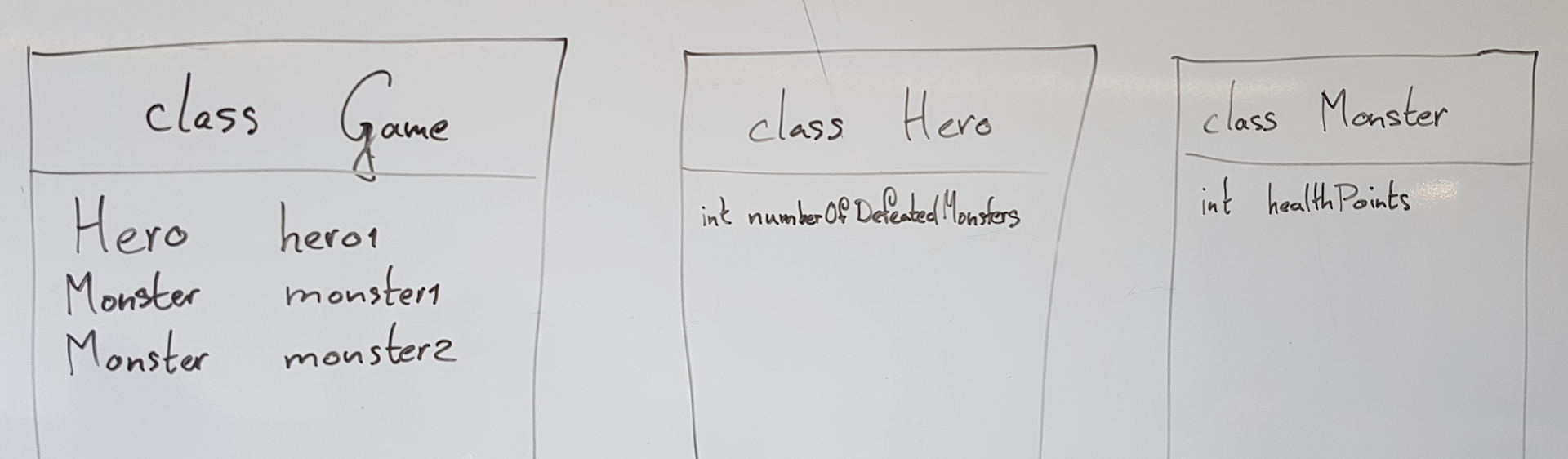

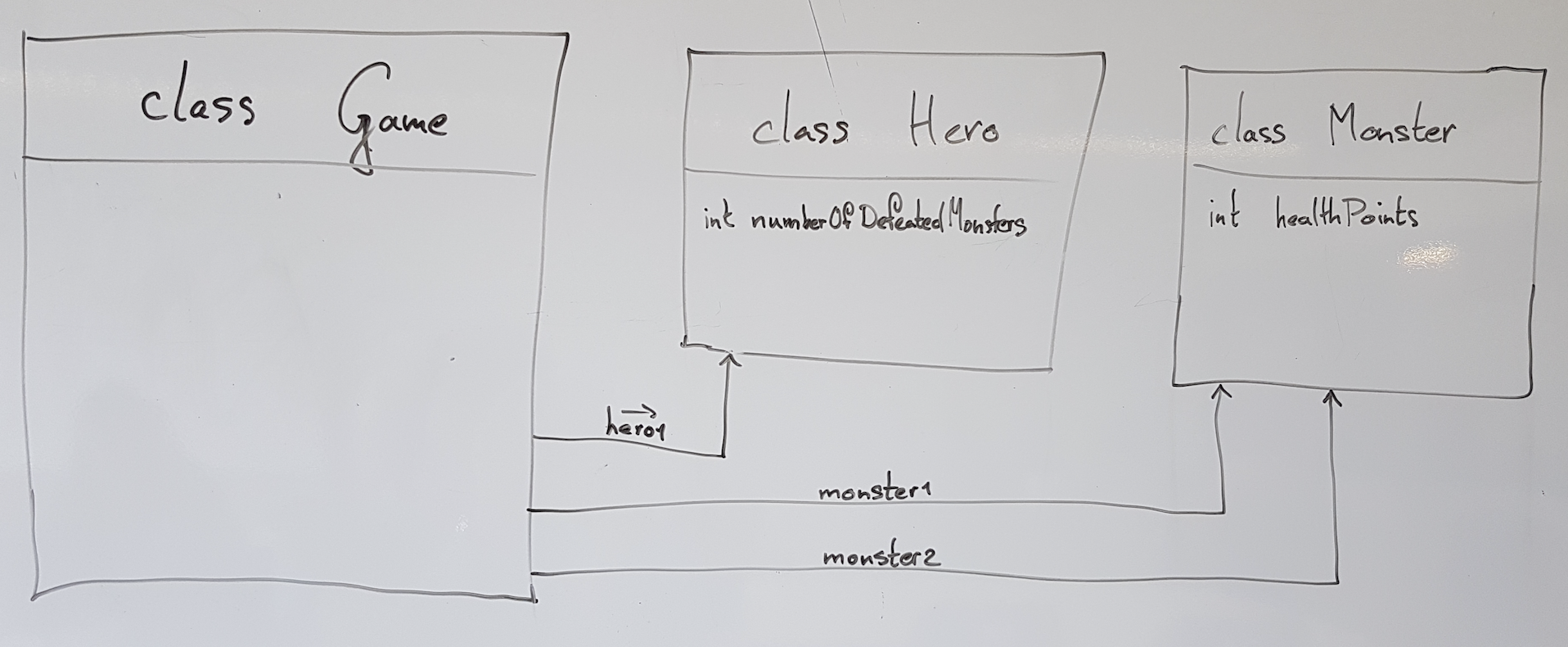

To do this, we create a Game object that contains

contains the references to all the heroes and monsters.

The code of the Game object will be in the class Game.

In class Hero is a Field

int numberDefeatedMonsters = 0;

created. This is because the hero would like the whole world to know how many

monsters have been defeated by him/her.

The Class Game has references to 1 hero and

2 monsters (monster 1 and monster 2) and to the before mentioned

type (those are the class names) you can tell that

the hero behaves as programmed in class ‘Hero’,

while both monsters behave according to the code in class Monster.

public Game()

{

Hero hero = new Hero();

Monster monster1 = new Monster();

Monster monster2 = new Monster();

}

Attack

Our hero is eager to start attacking a monster.

For this we are going to program behavior into the class Hero:

That is, on an object of type Hero you can

can call a method called Attack.

Furthermore, you tell which monster is being attacked and

How much damage (damage)

damage is inflicted on the monster (i.e. how much of the

hitPoints points are taken from the monster).

When the Attack method is called on a Held `object

the code of that method is executed.

The hero then calls the method LooseHealth from the bracketed monster.

method. Now we will code what that method

method can look like: for this purpose, we program the method

Attack in the class Hero.

void Attack(Monster monster, int damage)

{

monster.LooseHealth(damage);

}

or: if on an object of type Hero (because that class contains this code)

the Attack method is called (with as parameters in brackets

indicated in parentheses which monster and how much damage)

it calls the method LooseHealth

method of the specified monster. The incoming info

about the amount of damage is passed on.

In the method 2 so-called parameters are used, namely

sample of the type Sample and

damage of the type int (to be found between brackets after

the method name).

The word void means that no value is returned by the method,

There may also be instead of void a so-called return type indicating

what kind of value is returned.

In class Monster, the method LooseHealth must then be

must then be encoded:

void LooseHealth(int damage)

{

this.hitPoints = this.hitPoints - damage;

}

Explanation:

- Again, it starts with void because the method returns nothing.

- Then the method name LooseHealth.

- Between the brackets the one parameter, called damage and of type int.

- Between the curly brackets or curly brackets (‘{‘ and ‘}’) is an assignment:

- An assignment is identified by the = sign (pronounced wordt).

- To the right of the = is an expression, say a calculation, which is computed (evaluated). In this case,

this.hitPoints - damage. - The word this indicates that something is being done to the object we are now ‘in’: i.e., the specific monster that was attacked and thus passed as a parameter to method Attack. In method Attack you see that from * THAT* specific monster the method LooseHealth is called.

- Evaluation (calculation) of this.hitPoints gives the hitPoints number of that monster.

- The

- damage’ causes the given value of the parameter to be subtracted from this. - The value of this.hitPoints (to the left of the =) becomes the result of the calculation.

Construction of an object

Just as we can give additional information in the form of

in the form of parameters we can do the same when creating a new

of a new object. To do so, we use a constructor:

A constructor looks something like a method:

Sample(int initialHealth)

{

this.hitPoints = initialHealth;

}

A constructor can be recognized as follows:

- The constructor looks very much like a normal method, but….

- No

return-type(orvoid) is specified. - The name (Monster in this case) is the same as the name of the

class.

Constructor in Visual Studio

You can, of course, type the code above yourself (between the braces of the class)

but if you type ctor in that spot and then press tab twice

Visual Studio does some of the work for you.

Now if we call new Monster(125) from code an object

of type Monster is constructed and in front of it, after construction

the hitPoints value is set to the given number, 125 in this case.

With a constructor (just like with a normal method) you can also include

multiple parameters.

What do we have now?

We have now established a basis for a game in which a hero can attack monsters.

To get it working

We’ll explain why later, but just remember that we make every Field private.

Methods and classes may be private.

Code so far

For completeness, here is the code of the classes as described up to here.

First the class Game.

namespace HereComeTheMonsters

{

public class Game

{

public Game()

{

Hero hero = new Hero();

Monster monster1 = new Monster(125);

Monster monster2 = new Monster(100);

}

}

}

then class Hero

namespace HereComeTheMonsters

{

public class Hero

{

public Hero()

{

}

public void Attack(Monster monster, int damage)

{

monster.LooseHealth(damage);

}

}

}

and finally class Monster

namespace HereComeTheMonsters

{

public class Monster

{

private int hitPoints = 100;

public Monster(int initialHealth)

{

this.hitPoints = initialHealth;

}

public void LooseHealth(int damage)

{

this.hitPoints = this.hitPoints - damage;

}

}

}